Nampundi Marceline from Bibira died in November 2011 (photo taken by Nadine Grimm, May 2011)

The Gyeli language [ISO 639-3: gyi], also known under the name Bakola and many other spelling varieties such as Bagyele, Bajele, Gyele, Bogyiel, or Bagieli, is a Narrow Bantu (A801) language of the Makaa-Njem group (Gordon 2005, Maho 2009) in southern Cameroon. Speakers call themselves and their language Bakola in the northern part of the language area and Bagyeli in the central and southern part. Following Bantuist traditions, we refer to the people as Bagyeli and Bakola (depending on where the data was collected), dropping the Ba- prefix when we talk about the language Gyeli or Kola.

Estimates of the Bagyeli/Bakola population vary from 2,200 (Renaud 1976 :28) to 5,000 (Ngima 2001:215). Although they speak a Bantu language, they are not Bantu ethnically, but « Pygmy » forest foragers who have lived in symbiosis with sedentary Bantu-speaking communities over a long period of time. The Gyeli/Kola language as it is now spoken is closely related to Kwasio with its two dialects Mabi and Ngumba (also A80), the language of their former patrons.

Language contact and dialects

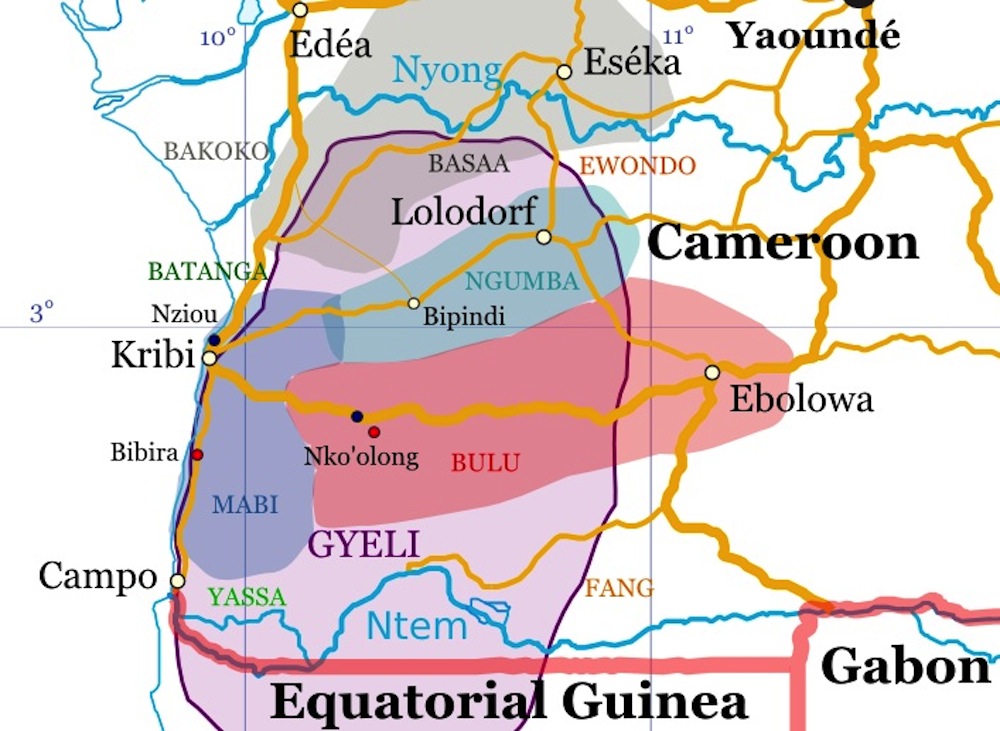

Gyeli/Kola is in contact with a multitude of different languages spoken by sedentary Bantu farmers. In the map below, these languages are represented by capital letters and include Bakoko, Basaa, Ewondo, Bulu, Fang, Yassa, Batanga, and Kwasio with its dialects Mabi and Ngumba. All of these languages also belong to the Bantu A group, though to different subgroups (A30, A40, A60, A70, and A80). This does not mean that each and every single Gyeli/Kola speaker is in contact with all of these languages, since the language zone is so large, about 12.500 km2 . Rather, Gyeli/Kola speakers are in contact with usually one main contact language.

The Gyeli/Kola speakers are currently shifting to the languages they are most closely in contact with. In the course of this language shift, different Gyeli/Kola dialects emerge. Already in 1976, Renaud (1976) reported of two dialects for the language: “Bajele” which was closely associated with Kwasio, and “Bakola” which was closely associated with Basaa (A40). As the Bagyeli/Bakola have become more sedentary since then and have entered into even closer relationships with other farming communities, the dialectal situation has become more complex. The Gyeli/Kola language is fragmenting as different communities of speakers borrow extensively from different neighboring languages, such as Kwasio (A8), Basaa (A40), Bakoko (A40), Yassa (A20), Ewondo (A60), and Bulu (A70).

In our project, we mainly investigate three of these dialects. Emmanuel Ngué Um, being a native Basaa speaker, works in the northern region which is in contact with Basaa, represented in grey on the map. The village, he is mainly working in, is called Lepdjom. Daniel Duke who has extensively worked on Kwasio (blueish shade) over the last years, investigates the Gyeli dialect in the Kwasio contact region around Lolodorf and along the coast, mainly in the village Bibira. Nadine Borchardt is in charge of the Gyeli variety in the Bulu contact area, represented by the red shade. “Her” village is called Ngolo. The two blue dots represent Bantu farmers’ villages where the linguists occasionally collect data for comparison with Gyeli/Kola.

Map of the Gyeli/Kola area and its neighboring languages (by Nadine Grimm, May 2012)

Language endangerment

The Bagyeli/Bakola have spoken a distinct language variety, that is not mutually intelligible with any of the other neighboring Bantu languages, for centuries, presumably since the Bantu migration (Bahuchet 2012). Now, however, they are shifting to the languages of their Bantu neighbors. Gyeli/Kola has become a highly endangered language for two main factors. The first one concerns the social status of the Bagyeli/Bakola among their neighbors and within the Cameroonian society. The Bagyeli/Bakola report that they are discriminated against by the farming populations because of their “primitive” lifestyle as hunter-gatherers, as it is perceived by the farmers, their poverty, and lack of education. These negative aspects are also attributed to the language. Thus, the language is used strictly for in-group communication and usually not spoken in public when outsiders are present (Duke, personal experience). When asked what language they speak, the Bagyeli/Bakola name the language of the villagers. They often even deny that they have a separate language of their own (Duke, personal experience). Bagyeli/Bakola have reported preferring to speak Kwasio when addressing outsiders (Ngima 2001:218).

The second factor concerns the Bagyeli’s/Bakola’s decreasing ability to continue their traditional lifestyle. Due to massive changes in their environment such as the inauguration of the biggest port in Central Africa in 2015, deforestation, expansion of palm oil plantations and the construction of more and more roads, the animals that the Bagyeli/Bakola depend on, disappear. As a result, they are forced to change their subsistence strategy, become sedentary and adapt more and more to a farming lifestyle. In the course of these changes, the Bagyeli/Bakola adapt to their neighbors who are already farmers and have more prestige than the hunter-gatherers, and shift to their languages.

The construction of the port has a big impact on some of the Gyeli villages. The village Bibira was relocated in spring 2012 to make way for the construction site. Before the relocation, the Bagyeli in Bibira lived right next to the road where trucks were passing every few minutes for many months. Their “new” Bibira consists of three wooden houses the Bagyeli are very proud of on a patch of former rain forest. The Bibira inhabitants report, however, that skin diseases have become more of a problem since they left the forest. They also worry that they will be relocated soon again because their new village is only temporary – the government has not yet found a permanent place for them.

Children in Bibira with a sign warning of the ongoing construction works of the port (photo by Nadine Grimm, May 2011)

The “old” Bibira, before the relocation of the village (photo by Nadine Grimm, May 2010)

Christopher Lorenz filming the construction site of the port in 2011 (photo by Nadine Grimm, May 2011)

The “new” Bibira, still close to the port and only a temporary settlement (photo by Nadine Grimm, July 2012)

References:

Bahuchet, Serge. 2012. Changing language, remaining Pygmy. Human Biology 84(1). 11–43.

Gordon. 2005. Ethnologue, the Languages of the World. Dallas: SIL

Guthrie, Malcolm. 1971. Comparative Bantu. An introduction to the comparative linguistics and prehistory of the Bantu languages, Part 1, vol. 2 : an outline of Bantu history. Farnborough, U.K.: Gregg International Publishers Ltd.

Ngima Mawoung, Godefroy. 2001. “The relationship between the Bakola and the Bantu people of the coastal region of Cameroon and their perception of commercial forest exploitation,” African Study Monographs. Suppl. 26 : 209-235.

Renaud, Patrick. 1976. Le Bajele: phonologie, morphologie nominale. Les dossiers de L’ALCAM. Vols. 1 and 2. Yaounde: ONAREST, Institue des Sciences Humaines.